Scientific Name: Leptailurus serval

Scientific Name: Leptailurus serval

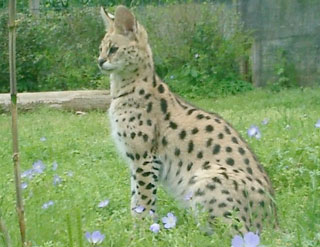

The serval is a medium sized African species averaging 20-30 pounds and standing 15-25 inches at the shoulder. It is a lanky species with noticeably long legs and neck and large ears in proportion to the rest of the body. It has a medium length tail about 8-12 inches long. The coloration is normally yellowish, with lots of black spots on the sides and stripes on the neck and shoulders. Other colors that have been found are melanistic (black), white-footed (varying from just the toes being white to the entire legs being white), and white. There are 14 currently recognized sub-species, but DNA testing may find, as with other feline species, that many of these may just be geographical populations and not separate sub-species. It is notable that individuals from more arid areas usually have larger, more pronounced spots than those from wetter regions.

Servals are usually found in the tall grass savannahs. The are absent from the central African rain forests and the Sahara desert. There is a small population in Northwestern Africa, and this population is considered very rare. Their main prey is small rodents, but birds, reptiles, fish, and insects are also taken. An interesting fact is that frogs seem to be a favorite prey. Geertsema (1985 in Ngorongoro, Tanzania) found the remains of frogs in 77% of 56 scats analyzed. She also observed a young male eat at least 28 frogs in a three-hour period. It has been extremely rare to find evidence of servals taking mammals larger than rodents.

The serval relies heavily on its keen sense of hearing to locate its prey. Once it has located something, the stalk ends in a high leaping pounce. These pounces can be as high as 3 feet and be as long as 3-12 feet. The serval will also make a high vertical leap when going after birds and insects, catching them with a clapping motion by the front paws or a downward strike, knocking the prey from the air. Most of the hunting activity takes place in the early morning or in the late evening.

Servals have no defined breeding season and may come into estrus at any time of the year. These heat cycles normally last for four days. Seventy-three days after mating, a litter of 1-4 kittens are born, with an average of 3. The kittens will be weaned at about 8 weeks of age and stay with their mother to learn life and hunting skills until they are 6-8 months old. They reach sexually maturity in 18-24 months, although some individuals may mature earlier and some later. They can live to be up to 20 years old.

The wild population status is good, though fragmentation is becoming a problem. However, servals seem to be adapting well to agricultural areas and the outlook is much better than for less adaptable species. The Barbary serval, from Algeria, is considered endangered by the USF&W Endangered Species Act. CITES lists all subspecies as protected under Appendix II for the purposes of international trade.

In captivity, servals are doing very well, being one of the most commonly kept feline species. ISIS lists over 300 kept in zoos throughout the world. Many more are kept in private hands both in Europe and North America. They breed well in captivity, although this was not always the case. The first documented breeding of the serval in North America took place at the St. Louis Zoological Park in 1956. At that time, breeding was considered quite an accomplishment and it wasn’t until several years later that breeding became commonplace. The AZA has started a Population Management Plan (PMP) for the captive management of servals and has established a studbook in an attempt to keep genetic viability within the species.

Servals require minimal special care. Being an African species, they do appreciate a warm nest box in cold weather, but they can take quite cold weather. They eat 1-3 pounds of meat per day.

Conservation concerns in the wild center on wetlands preservation, since servals seem to prefer areas near water. There is still a small trade in pelts and meat, but it appears that this is mainly for domestic ceremonial or medicinal purposes or for the tourist trade. There is very little international trade in serval pelts. Several countries also allow the sport hunting of servals for trophies, but this is regulated and doesn’t seem to be detrimental to the population as a whole.